Family History

Food brings families together.

Picture a three-year-old glued to the TV set…watching Julia Child. That was me. I eagerly waited for The French Chef to come on the TV every day, in between my cartoons. Influenced by what I watched Julia make, when the day came when someone at home would ask me what I wanted from the grocery store, I would respond “smoked oysters and olives”; which I needed to make my “hors d’oeuvres”. The looks I got…they were expecting me to say candy and gum!

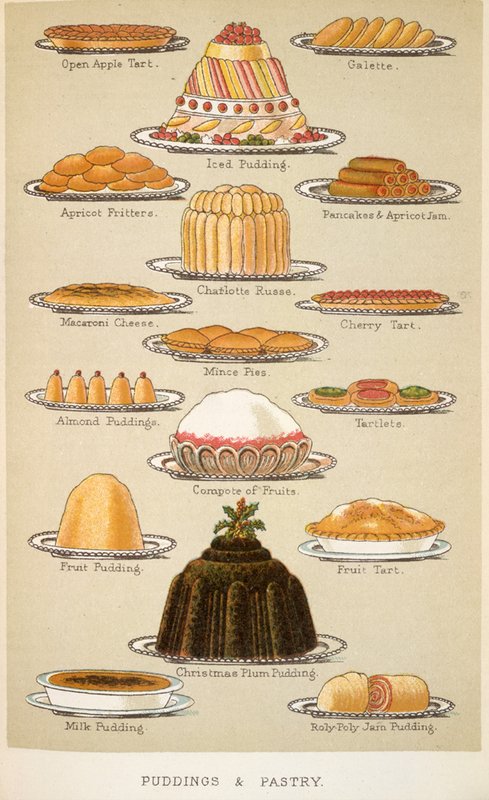

Every weekday afternoon we would have family and visitors stop by for coffee. I can remember to this day dragging the heavy wrought iron chair from the kitchen table over to the counter so I could climb up and get to work. In reality, I was whipping up a batch of Ritz Crackers with peanut butter, or Saltines topped with a smoke oyster. I’d take my mom’s fancy cocktail toothpicks and stab an olive or pickled onion, then place it in the center. Voila! My platter was ready to be served. All in all it was pretty 1968 Chic! I would often read through my mother’s 1953 edition of Better Homes & Gardens “New Cookbook” and my oldest sister’s 1955 edition of “Better Homes and Garden’s Junior Cookbook, for the Hostess & Host of Tomorrow”, and dream about making those recipes. I remember when I (finally) received my first cookbook: “The Pooh Cook Book”; published in 1969 and written by Virginia H. Ellison. Each of those books live on a special spot on my bookshelf to this day. Every now and then I still pull them out; every photo and description still familiar.

The real influence on my passion for cooking is a story in itself. So, let’s go back…way back. There are three women who have had the most influence on me: Eliza Seymour Lee, Dorothy Jones Langston and Celestine Noisette. Celestine was one of my paternal ancestors who came to Charleston, South Carolina via Haiti in the late 1790’s. Eliza was my great, great, great, great grandmother, also on my paternal side who lived in Charleston. Finally, Dorothy Jones Langston, aka “Aunt Dolly” was my maternal grandmother who lived on a rural farm in Sunbury, North Carolina.

Eliza Seymour Lee was a renowned and highly successful pastry chef, and the daughter of famed Charleston cook Sally Seymour [1779-1824]. Eliza was considered Charleston’s very own First Top Chef. The famous Nat Fuller (The Bachelor’s Retreat, 1865) was one of Eliza’s apprentices. Together with her husband John Lee, a tailor and savvy businessman, Eliza owned and operated multiple dining establishments in Charleston before the American Civil War. From 1840 through 1851, the couple collaborated in running four famous establishments and a location that was rented out for meetings.

Eliza also took in boarders and vended pastries, cakes, and savory pies to the public. I loved that she became so successful in her catering and hospitality ventures. Her husband John quit his job to assist her! My favorite story about Eliza was written in Marina Wikramanayake’s book, A World in Shadow: The Free Black in Antebellum South Carolina (1974). In the book she says, “Mrs. Lee bequeathed the state something more tangible than a reputation for good cooking. According to tradition, her two sons went North to seek their fortunes and, when hardship threatened, resorted to the art their mother had taught them. News of their method for picking and preserving soon reached the ears of an enterprising man named Heinz, who bought their recipes and rights. South Carolina’s contribution to the “57 Varieties” distributed today by J. H. Heinze & Company thus goes back over a hundred years to a very enterprising free black woman”.

Every year we would go to my (maternal) grandparents’ farm in Sunbury, North Carolina. There, I would watch my grandmother, Dolly, cook three meals a day for the family, specifically for my grandfather and his farm workers (which included my uncle), as well as for friends and extended family passing through the little town. My grandfather, Carl Langston, owned and worked the farm, which produced hogs, peanuts and soybeans. In the 1940s and 1950s their farm was the largest producer of peanuts for Planters Peanuts, which at the time was located thirteen miles away in Suffolk, Virginia. He also supplied thousands of pounds of pork for Smithfield Hams, located up the road in Smithfield, Virginia. Here is where I learned to love to cook. My grandmother would often let me cook along-side her, giving me age-appropriate tasks and duties to complete. To this day there are few things I remember hating more than shelling a bushel of butter beans! As I grew up, I started to write her cooking tips and recipes down. I later realized that I was the only one in the family that had these culinary treasures. Day after day she would produce these elaborate meals, with homemade biscuits and bread served at each. Keep in mind, “Supper” as the evening meal was called, was often something light or a left-over piece of fried chicken from lunch pulled off the bone and made into a sandwich. My favorite supper was compiled of one of her breakfast biscuits split open and buttered. To this she would add two slices of sharp cheddar cheese and then place it under the broiler to melt. A dollop of her homemade famous strawberry preserves or watermelon rind preserves on top was really good!

If she wasn’t in the kitchen preparing meals or baking, you could find her twice a day feeding and picking up the eggs from over her 100 hens, or with a cane, walking slowly down the dirt lane to her strawberry patch in the Spring, Summer or Fall. She would use all the strawberries she picked for her highly-desired preserves.

To my knowledge, Celestine Noisette did not have a reputation for being in the kitchen or entertaining. I am sure she brought her most treasured recipes with her to America from Haiti; I feel assured that there were a few pickling recipes as well included in her cache. Sadly, her recipes have been lost to time, so I can only assume what she cooked. However, she influenced me in other ways. First and foremost – she was incredibly brave and tenacious. As the historical records tell us, because of the miscegenation laws of South Carolina, her French husband Philippe was forced to declare her as his slave upon their ship’s arrival into the Port of Charleston. The six children they had together would also became his slaves. Shortly before his death, in 1835, Philippe petitioned the state of South Carolina to emancipate his family, but it was denied. Celestine continued to fight for her children and their family business; later succeeding in convincing the court to emancipate them all. She stayed in Charleston until her death in 1853.